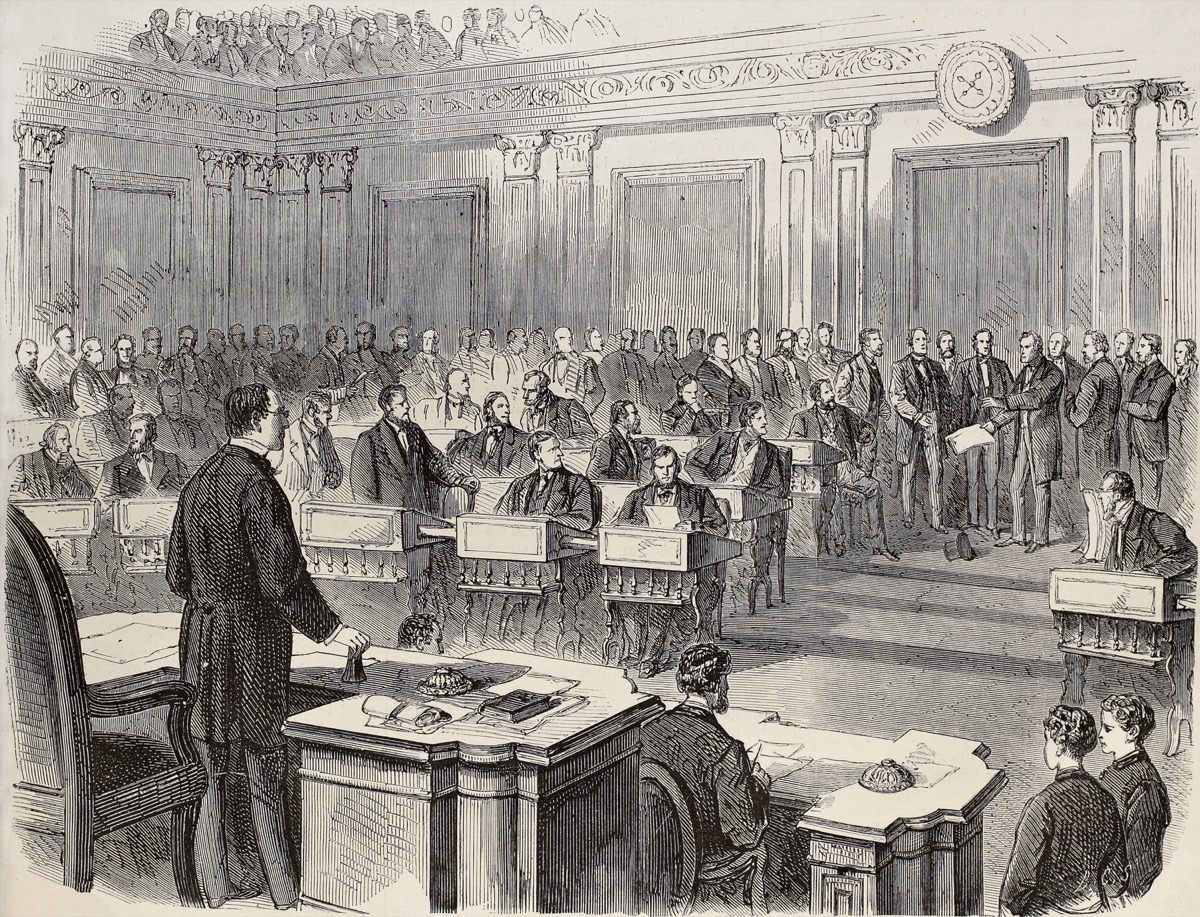

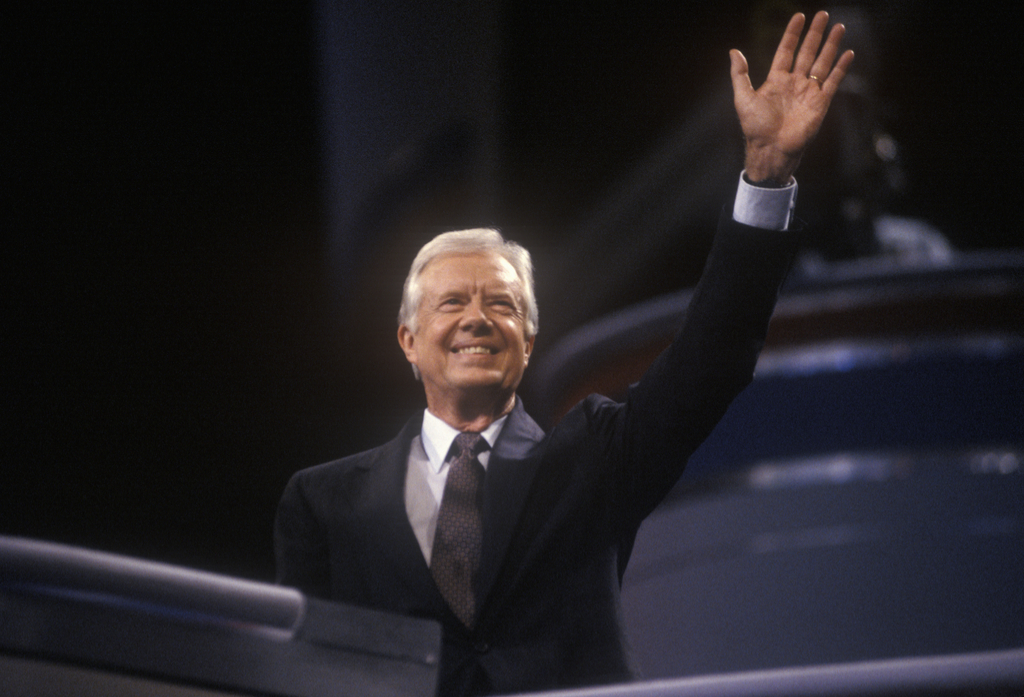

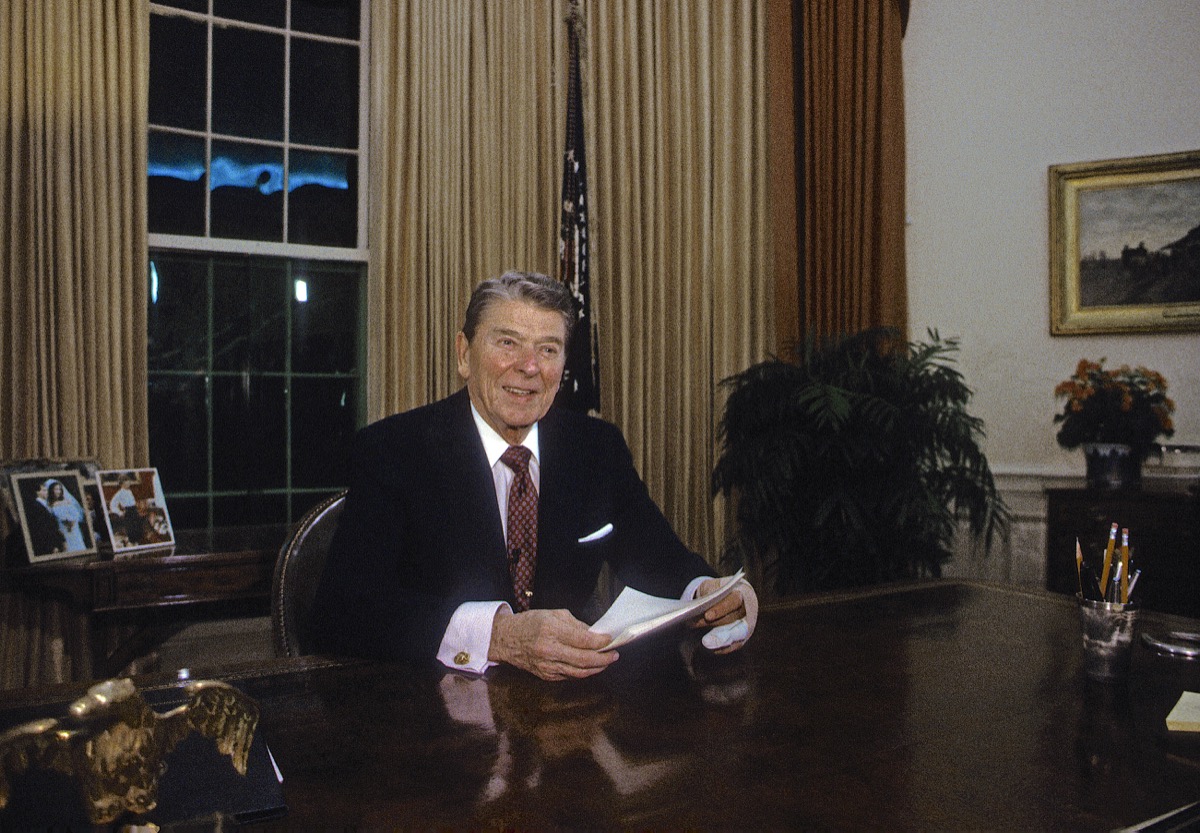

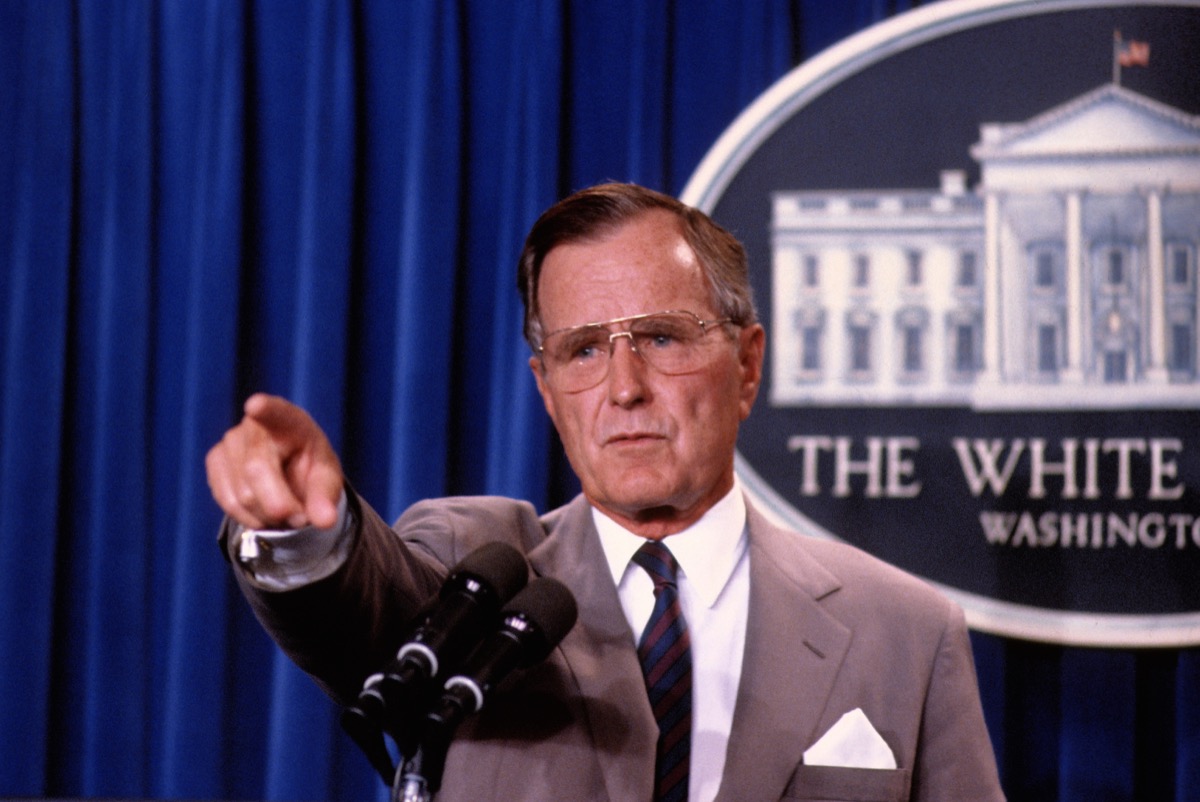

The U.S. Constitution only vaguely outlined presidential succession in Article II, Section 1, Clause 6. The 83-word blurb stated that power would be transferred to vice presidents in the event that a president was removed because of “Death, Resignation, or Inability to discharge the Powers and Duties of the said Office.” In the same clause, Congress was granted the power to instate a president if both the president and vice president were removed. But the processes of how that would be accomplished were not clearly outlined. And for more fascinating trivia about our nation’s leaders, check out 30 Amazing Facts About U.S. Presidents You Never Knew. The order of succession has flip-flopped throughout the years. In the second session of Congress in 1792, the Presidential Succession Act was passed. It modified the original Constitutional plan by adding two leaders of Congress—the Senate president pro tempore (“for the time being”) and the House speaker—to the line of succession. They were then removed from the line in 1886 and replaced with the entirety of the president’s cabinet. In 1947, the leaders of Congress were reinstated ahead of the cabinet members, and the speaker was placed ahead of the president pro tempore. So the order now goes vice president, House leader, Senate leader, cabinet. The Senate leadership is divided between the vice president and the president pro tempore, who, as the title indicates, acts as the Senate leader when the vice president is unavailable. Between 1886 and 1947, the president pro tempore was third in line for the presidency. After Abraham Lincoln was assassinated in 1865, his vice president, Andrew Johnson, took over as president. When Johnson was impeached three years later, that left Benjamin Wade of Ohio in direct line to the presidency. Johnson, however, was acquitted in the Senate when it failed to reach the two-thirds majority needed to convict, and Wade therefore never assumed the position of president. And to see how our current president addressed COVID and the beginning of the pandemic, check out President Trump Releases New Guidelines to Slow Coronavirus Spread. Under the terms of Section 3 of the 25th Amendment, which was ratified on February 10, 1967, vice presidents temporarily assume the power of the presidency if the president is incapacitated and unable to perform his duties. Jimmy Carter contemplated transferring power in 1978 when he needed to have hemorrhoid surgery. A letter of the transfer of power was drafted but not implemented, as Carter was never deemed unable to perform the duties of president because of the surgery. Section 3 is also often referenced in the report of a president’s annual checkup. Take this 2010 report of Barack Obama’s physical, in which his doctor writes: “At no time was it necessary to temporarily transfer Presidential authority under Section 3 of the 25th Amendment.” Section 4 of the 25th Amendment allows the president’s cabinet to transfer power from the president to the vice president in the case that the president is incapacitated and can’t himself voluntarily invoke Section 3. When Ronald Reagan was shot on March 30, 1981, his cabinet drafted the appropriate letter that would transfer power to George H.W. Bush, but they decided not to sign it or deliver it to Congress. Reagan was back working the day after he was shot, and was back in the White House within two months. And for more famous figures that have struggled with serious health problems, check out Celebrities Who Battled Cancer and Won. While president, Ronald Reagan underwent surgery for colon cancer on July 13, 1985. Before doing so he invoked Section 3 of the 25th Amendment and he sent letters to Congress officially making Vice President George H.W. Bush the acting president while the surgery took place. Power was transferred back later that day—with Bush’s time in power lasting from 11:28 a.m. to 7:22 p.m. When George W. Bush was the 43rd president, he twice made Dick Cheney, his controversial vice president, the official acting president of the United States. The reasons were routine: Bush underwent two colonoscopies during his double-term in office—on June 29, 2002 and on July 7, 2007—and was sedated during each. Cheney was acting president for a total of about four and a half hours. During his brief stint as commander in chief, Cheney penned a letter to his grandchildren as “a souvenir for them to have down the road someday.” The first president to die in office was William Henry Harrison, who passed only 31 days into his presidency in 1841. Harrison’s death has long been attributed to pneumonia he supposedly caught during his long inaugural address given in the cold, but some historians now contest that fact, suggesting contemporary medical practices played a hand. Harrison’s vice president, John Tyler, assumed the presidency against some opposition from the former president’s cabinet, who wanted Tyler to remain “vice president acting as president.” In 1850, Zachary Taylor died due to undiagnosed intestinal issues that may have started during an Independence Day celebration. After Millard Fillmore took the oath of office, Taylor’s cabinet resigned so Filmore would have the “opportunity to set his own course.” In 1923, Warren G. Harding suffered a heart attack while his wife read him The Saturday Evening Post in a San Francisco hotel room. Calvin Coolidge, Harding’s vice president, was administered the oath of office by his father, a notary public, at the family home in Vermont. After his death from a cerebral hemorrhage while sitting for a portrait in Warm Springs, Georgia, in 1944, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s vice president, Harry S. Truman, suddenly became the leader of the free world during World War II. Of the immeasurable responsibility, Truman said, “I felt like the moon, the stars, and all the planets had fallen on me.” In 1865, five days after the end of the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln was shot with a pistol while attending the theater. Vice President Andrew Johnson was also a target in the assassination plot, but was saved due to the shooter John Wilkes Booth contracted to kill him being “incompetent at conspiracy.” He apparently spent the day drunk in the lobby of Johnson’s hotel. James Garfield was shot twice in a waiting room at a Washington, D.C., train station in 1881. After the first shot grazed his arm, a second hit him in the back. Garfield lingered for more than two months before dying from an infection. Chester A. Arthur was given the oath of office at his New York City residence the day after Garfield died.ae0fcc31ae342fd3a1346ebb1f342fcb In 1901, William McKinley was shot twice by an anarchist while he was visiting an exposition in Buffalo, New York. Vice president and passionate outdoorsman Theodore Roosevelt was on a family retreat when McKinley died, hearing the news as he returned from climbing the highest mountain in the Adirondack Mountains. He was sworn in as president the same day. Following the famously tragic assassination of John F. Kennedy in Dallas in 1963, Lyndon B. Johnson, standing next to newly widowed Jackie Kennedy, was sworn in as president 98 minutes later aboard Air Force One. When Richard Nixon resigned the presidency in disgrace on August 9, 1974, he did so with a simple letter stating, “I hereby resign the office of the President of the United States,” which was initialed by his witness, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger at 11:35 a.m. His successor, Gerald Ford, released his own statement when he was sworn in exactly a half hour later at 12:05 p.m., which included this famous line: “My fellow Americans, our long national nightmare is over.” Despite that condemnation, Ford also asked Americans to pray for Nixon, writing, “May our former President, who brought peace to millions, find it for himself.” And for more historical facts and the latest news delivered straight to your inbox, sign up for our daily newsletter. Modern presidents draft letters of succession—the actual notes that would go to Congress in the case they are incapacitated—just in case. Copies are kept on hand so that the president can sign and date them in an emergency situation. The contingency plan includes copies stashed at “the White House Counsel’s office, presidential emergency facilities, Air Force One and Two, and inside the nuclear football, which travels with the President and Vice President.” During the attacks on the World Trade Center in New York City, President George W. Bush boarded Air Force One, but unfortunately his lines of communication to senior military officials were “cutting out.” Because he was essentially out of the loop on any early response to the attacks, scholars noted that there needs to be a plan for every contingency: “Profoundly consequential decisions might be impeded or made by individuals who are not clearly authorized to do so.” In 2017, scholars gathered at the Fordham University School of Law to discuss possible changes to the laws put in place in 1947. They published a paper that details all the existing flaws in the succession plan as well as any ambiguity in the language. Additional reporting by Alex Daniel.